Alpha Motor Neurons

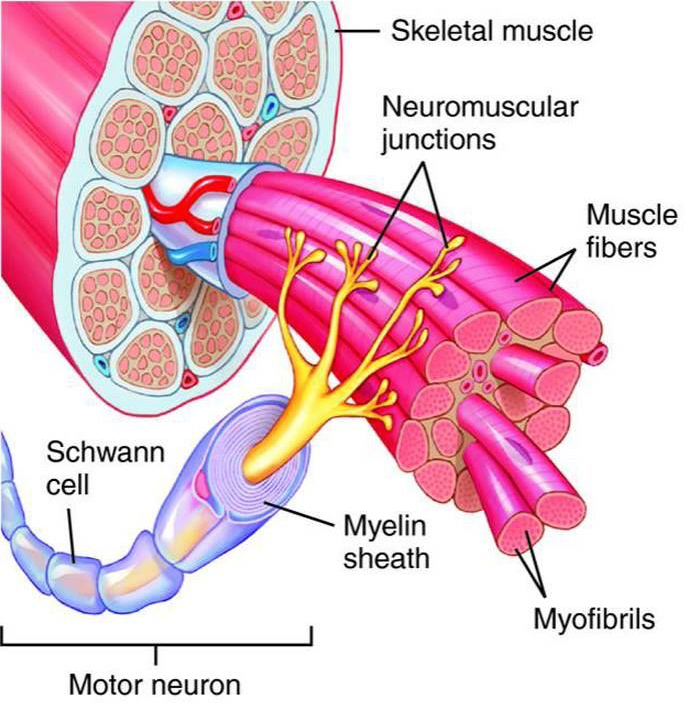

Alpha motor neurons (also called lower motor neurons) innervate skeletal muscle and cause the muscle contractions that generate movement. Motor neurons release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine at a synapse called the neuromuscular junction. When the acetylcholine binds to acetylcholine receptors on the muscle fiber, an action potential is propagated along the muscle fiber in both directions. The action potential triggers the contraction of the muscle. If the ends of the muscle are fixed, keeping the muscle at the same length, then the contraction results on an increased force on the supports (isometric contraction). If the muscle shortens against no resistance, the contraction results in constant force (isotonic contraction). The motor neurons that control limb and body movements are located in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, and the motor neurons that control head and facial movements are located in the motor nuclei of the brainstem. Even though the motor system is composed of many different types of neurons scattered throughout the CNS, the motor neuron is the only way in which the motor system can communicate with the muscles. Thus, all movements ultimately depend on the activity of lower motor neurons. The famous physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington referred to these motor neurons as the “final common pathway” in motor processing.

Motor neurons are not merely the conduits of motor commands generated from higher levels of the hierarchy. They are themselves components of complex circuits that perform sophisticated information processing. Motor neurons have highly branched, elaborate dendritic trees, enabling them to integrate the inputs from large numbers of other neurons and to calculate proper outputs.

Two terms are used to describe the anatomical relationship between motor neurons and muscles: the motor neuron pool and the motor unit.

Motor neurons are clustered in columnar, spinal nuclei called motor neuron pools (or motor nuclei). All of the motor neurons in a motor neuron pool innervate a single muscle, and all motor neurons that innervate a particular muscle are contained in the same motor neuron pool. Thus, there is a one-to-one relationship between a muscle and a motor neuron pool.

Each individual muscle fiber in a muscle is innervated by one, and only one, motor neuron (make sure you understand the difference between a muscle and a muscle fiber). A single motor neuron, however, can innervate many muscle fibers. The combination of an individual motor neuron and all of the muscle fibers that it innervates is called a motor unit. The number of fibers innervated by a motor unit is called its innervation ratio.

If a muscle is required for fine control or for delicate movements (e.g., movement of the fingers or hands), its motor units will tend to have small innervation ratios. That is, each motor neuron will innervate a small number of muscle fibers (10-100), enabling many nuances of movement of the entire muscle. If a muscle is required only for coarse movements (e.g., a thigh muscle), its motor units will tend to have a high innervation ratio (i.e., each motor neuron innervating 1000 or more muscle fibers), as there is no necessity for individual muscle fibers to undergo highly coordinated, differential contractions to produce a fine movement.